High-Low, High-Low, It’s Off To Work You Go

Posted on Sep 5, 2020 in Editorials | 1 comment

Earlier this week, I had the pleasure of editing Daniel Ho’s theories on crossovers as reflections of the zeitgeist. In his thoughtfully-written piece, Daniel argues that crossovers are chimeras, reflecting a social trend towards generalized products that combine social signaling attributes from multiple socio-economic categories. The crossover, therefore, is the “blazer and jeans” look, offering broader but shallower capabilities than the specialized vehicles that preceded it.

It is my hope that Daniel, and the rest of the B&B, will take it as a signal mark of my esteem and admiration for the both the substance of Daniel’s original argument and his stylish manner of expressing it when I say that he is absolutely, completely, thoroughly wrong.

I’ll start by saying: yes, High-Low is really “a thing” in the fashion world and was a thing long before there was such a phrase to describe it. I will also suggest that High-Low has long had a place in the automotive world. The original Mini, which was owned and driven by everyone from rural pensioners to Paul McCartney and Enzo Ferrari, was an example of “fast fashion” with universal appeal. In the United States, the original Beetle had similar mojo, although it’s worth noting that elsewhere in the world the Type I VW was a simple and depressing statement of poverty and perhaps that’s why Europeans don’t get excited about the various New New Beetles.

It’s tempting to ascribe the ’90s body-on-frame SUV boom to a similar “High-Low” spirit, but it would be wrong. Much of the chic appeal of the Grand Wagoneer et al. came from the fact that it was closely associated with the country homes of the wealthy; this was also the secret of the Range Rover’s upscale credibility. It’s hard to believe it in 2016, but there was once a time that driving a Rangie in the City of London directly implied that one was to the manor born, as it were. Similarly, the possession of a trimmed-up Suburban in the United States suggested the simultaneous possession of horses.

Yet the SUV would have remained a curiosity had it not been the beneficiary of a perfect storm in the auto industry. The cars offered by the Detroit Three in 1992-1994 were mostly based on platforms that had been conceived in the darkest days of the Carter/OPEC oil crisis. They were also CAFE-conscious. But the price and artificial scarcity of oil never quite returned to their late-’70s levels. So customers who had no fear whatsoever of rationing or $5/gallon gasoline bounced over to their local dealers to buy a new car, at which point they were faced with a wide array of depressing shitboxes like the Ford Tempo and the Chevrolet Celebrity.

The Ford Explorer and Jeep Grand Cherokee were not good vehicles in any sense of the word. Trust me. I sold ’em when they were new. But to buyers who were absolutely horrified at the prospect of having to drive a Cutlass Ciera for the next 80,000 miles, they were characterful, rugged, durable alternatives. The vast majority of Explorer buyers I met during 1995 and 1996 would have been better-served by a Taurus wagon — but just 10 minutes listening to the front subframe of a Taurus crash and bang around on their test drives made the case for the truck.

What happened next was exactly the same thing that had happened during the personal luxury coupe explosion of the ’70s: The people with the most financial freedom were early SUV adopters. Their neighbors envied their acquisitions and slavishly imitated their betters. Before long, everybody had a body-on-frame SUV. Consequently, non-prestige cars acquired the stigma of being prole-mobiles. After all, the last people in any middle-class neighborhood to own a conventional automobile were, by definition, the poorest people in that neighborhood and the ones who therefore had held on the longest to their pre-SUV-era vehicles.

I need make no other case for the ascent of the crossover than this: it offers the same driving position and perceived capability of the SUV, but at a lower price. The Lexus RX300, the ur-crossover, was successful because it was massively cheaper than the Lexus body-on-frame SUVs while managing to send about the same social image to everybody who did not have an address in Martha’s Vineyard or Telluride.

The historically astute or just plain old readers among the B&B will recall that the 1969 Pontiac Grand Prix and 1970 Chevrolet Monte Carlo featured extra-long hoods that gave them the presence of a full-sized coupe at the price of a mid-sized coupe, thus creating the PLC phenomenon.

The story of the crossover thus far has been a blow-by-blow recapitulation of the PLC’s rise to dominance in the ’70s. In 1977, the best-selling car in the country, the Cutlass Supreme, was primarily delivered as a long-hood coupe. When the RAV4 or CR-V finally assumes the title of best-selling “car,” we’ll know that we are in the 1977 of the crossover era.

You can see, therefore, that we need not have recourse to any sort of specific “fashion theory” to explain the crossover. It is to the SUV what the PLC was to the big coupes of the ’60s: the same look and feel, but for less money. It is the cheapest way to have approximately what everybody else has.

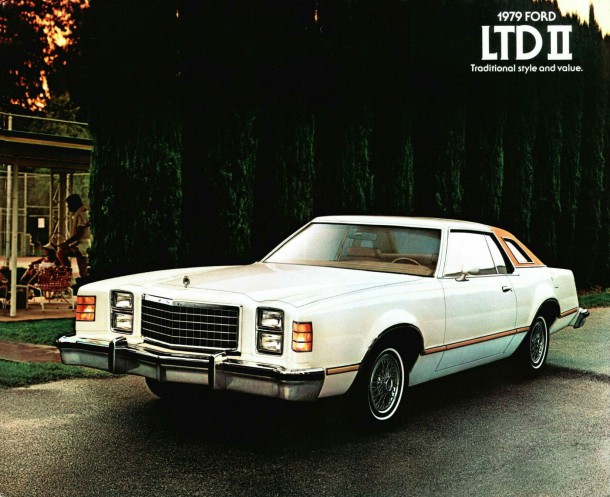

This also explains why all crossovers look exactly the same; they’re meant to, because having a crossover that looks unique defeats the point of having what everybody else has. Those readers who are feeling unnecessarily sanctimonious about the abject similarity of the Santa Fe and the X3 and the RAV4 and the Equinox and the rest should take a look at pictures of the late-’70s PLCs and see how well they can distinguish a 1978 from a 1977 Monte Carlo from a 1978 LTD II.

Only two things separate the crossover phenomenon from that of the PLC. The first is sex. Or gender, if you insist on using the wrong word. Forty years ago, most purchase decisions were made by men. No surprise, then, that personal-luxury-coupes are basically dicks on wheels. Remember that the artificially long hood is the defining characteristic of the PLC. Crossovers, on the other hand, are exclusively purchased by women and the men who can’t stand up to them. No authentic man has ever had any genuine feeling for a modern crossover, any more than he would have a settled opinion on a panty liner. Women buy the things and therefore they are cocoons that suggest height and protection and safety and capability in reserve.

The second difference between 1976 and 2016 is something I can only call give-a-damn. Nobody gives a damn about cars any more. It is understood by the reader that the “nobody” to which I refer includes him, the same way that if I wrote “Nobody truly cares about Twilight Sparkle” on a “subreddit” it would be generally true no matter how many thousands of “bronys” there are in this country.

People used to buy cars a lot more frequently than they do today. Cars cost less and factory work paid more and, in any event, you couldn’t expect that a car would last very long before requiring extensive refurbishment or outright replacement. The American Dream was generally interpreted to mean moving out of a shithole apartment in New York to a comfortable suburban home, not the inverse. Young people wanted to have adventures in their cars because Tinder didn’t exist and parents didn’t let you have sleepovers with your high-school non-gendered bi-sex otterkin sex partner like they do today.

No wonder, then, that the ’77 Monte Carlo was styled at the expense of all else. Even if the style was, frankly, odious — it was style. Today’s crossovers are meant to be non-styled. They’re the equivalent of that “Soylent” stuff that programmers are supposed to drink at their desks so they don’t accidentally see the sun through a cafeteria window and turn into dust. It’s all the car you need. All the car you’re supposed to have. And, eventually, all the car you’ll be permitted to buy.

.gif)

A vehicle can easily cost a billion bucks to develop. Unless your OEM is staring at the abyss of bankruptcy, it’s probably wise to increase the odds of having a successful investment by not taking too many risks.