The Tale of the Round Door Rolls-Royce

Posted on Sep 18, 2021 in Editorials | 1 comment

I’ve tangentially touched on the topic of this post, the famous art deco “Round Door Rolls-Royce”, before when discussing Audi advertising and some Detroit history. On my recent trip to Los Angeles to drive a McLaren 675LT (you think Jack Baruth is the only TTAC staffer who can swing the loan of a supercar?), I took the opportunity to visit the newly renovated Petersen Automotive Museum and the unusually bodied Rolls happened to be on display right where you walk into the building.

It’s a striking looking car, to say the least, and a multiple show winner undoubtedly worthy of historical note. Almost more interesting than the car, though, is the way its tale is presented and what that teaches us about the way ideas get entrenched, how a single facet of a story can obscure its context.

The first Rolls-Royce Phantom — then called the New Phantom, presently called the Phantom I — was introduced in 1925 in response to competition from European luxury marques like Hispano-Suiza and Isotta Fraschini and from premium American automakers like Packard and Pierce-Arrow. Based on the chassis of the outgoing 40/50 model, now known as the Silver Ghost, the Phantom introduced Rolls-Royce’s first overhead valve engine and four-wheel brakes (although some sources say front brakes were introduced in late production Silver Ghosts). The OHV engine was taller than the sidevalve motor. That affected styling. The bodies coachbuilt for the Phantom I had higher hoods, radiator shells and cowls.

This particular 1925 Phantom I chassis, when new, was sent by the factory to London coachbuilder Hooper & Company, which gave it one of their cabriolet bodies. The buyer was a “Mrs. Hugh Dillman of Detroit,” as just about every source from The Old Motor to the Petersen museum that currently owns the car puts it. For some reason, the Phantom was never delivered to the United States. It’s thought Mrs. Dillman either didn’t like the body or simply exercised what was then called a woman’s prerogative to change her mind. Whatever the reason, she didn’t consummate the purchase and the car was instead sold to the Raja of Nanpara, who took it back to India. After passing through a series of owners, it ended up in Belgium in the early 1930s.

In 1934, an as-yet-unidentified owner took the Phantom to the Jonckheere body company near Roeselare, Belgium to be rebodied. Though Henri Jonckheere built his first luxury automobile in 1902, the company had transitioned to making mostly bus and coach bodies by the 1930s. It still exists today as VDL Jonckheere.

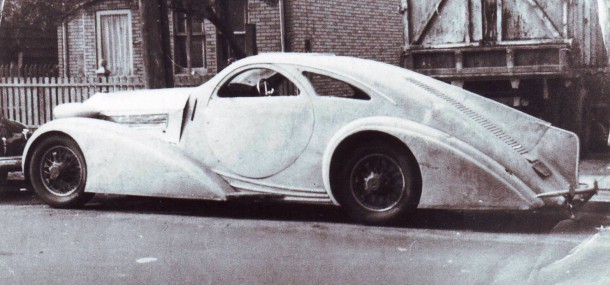

It’s not known who designed it, but Jonckheere built a radically different coupe body. Some say it was inspired by the aero designs of stylists Jacque Saoutchik and Joseph Figoni — but, to my eyes, it’s not nearly as elegant and flowing as their work. The squarish Rolls-Royce grill was retained, but it was sloped back to give the tall grill a more streamlined look. It is perhaps the only classic era Rolls-Royce whose grill is not vertical. To say the least, the car is a bit controversial with traditional Rolls-Royce enthusiasts. The windshield is also steeply raked. Bullet headlights and very long and flowing fenders continue the streamlined theme, but the car is so massive it’s hard for me to call it sleek. To finish off the aero look, Jonckheere put a big tailfin down the length of the middle of the trunk lid. Such fins were popular with European coachbuilders in the 1930s and you can see them on Bugattis, Delahayes and other custom-bodied cars of the era. Designer Raymond Loewy added one to his customized 1939 Lincoln Continental.

Of course, the Rolls’ most distinctive features are its large rear-hinged round doors, which allow ingress for both front and rear passengers. Because of the odd door shape, the side windows are split vertically and open up like a scissors as they retract into the doors. Round fender skirts for the rear wheels echo the shape of the doors.

A fire destroyed Jonckheere’s records in the late 1930s, so it’s not known just who commissioned the custom body, nor who designed it.

The car is almost 20-feet long and finished in dark black. It’s a big, almost ominous looking vehicle that would be at home in a Batman movie, driven by the villain.

It’s not a very practical car. With ponderous weight and no power assist, the steering is difficult, particularly at low speed. The non-synchro transmission needs to be double clutched and, even though the car features Rolls-Royce’s servo-assisted mechanical brakes, the weight makes it hard to stop. The large turning radius, low ground clearance and extended rear end make maneuvering the vehicle difficult. The steeply sloping fastback roofline forces rear passengers to slouch. There is no back window to speak of, just louvers, so visibility isn’t the best. To make the most of the limited trunk space, there is a set of fitted luggage.

However, as someone at the Petersen mentioned to me, the Jonckheere coupe was not built to be driven on actual roads, the turning circle alone makes that a chore. It was built to drive onto the show field, win ribbons, and then put back into storage. Soon after it was built, it won the Prix d’Honneur at the 1936 Cannes Concours d’Elegance. It then passed through a number of owners before it ended up in the United States in the possession of New England light bulb magnate Max Bilofsky. Despite its lack of practicality, Bilofsky was apparently chauffeured around Bar Harbor, Maine in the Rolls Royce.

Somehow the car survived scrap metal drives during World War II, but did end up in a New Jersey scrap yard in the early 1950s. Pioneering classic car enthusiast and entrepreneur Max Obie discovered the car, then nearly derelict, and started to fix it up. If the car wasn’t enough of a spectacle, Obie had it painted with real gold flake, made up a story that it was formerly owned by King Edward, who abdicated to become the Duke of Windsor, and put the gold “Royal Rolls” on tour, charging a fee to look at the interior.

The car again changed hands a few times, but remained on the East Coast, eventually acquiring an off-white exterior color. At the peak of the early 1990s’ collector car bubble, a Japanese collector paid $1.5 million for it at auction. It sat in his collection, mostly forgotten, for almost a decade. The Petersen museum bought it in 2001.

The curators and restorers at the Petersen discovered that the paint wasn’t the only thing that had changed since 1935. The Petersen completed a period correct restoration. While no color photographs of the car’s exterior exist from the 1930s, the Petersen had it finished in black, deciding that color highlighted the car’s distinctive shapes best.

Considered to be one of the Petersen’s jewels, it’s one of the few cars from the museum’s own collection that were put on display after the renovation. Most of the cars now on display are loans, with the vast majority of the museum’s own cars being stored downstairs in the basement “vault.”

As the car was built to be shown, that’s exactly what the Petersen museum has been doing since the restoration. It has won the Lucius Beebe Trophy for the best Rolls-Royce at Pebble Beach and it won the People’s Choice Award at the former Meadow Brook concours, now the Concours of America at St. John’s.

It was appropriate that the round door Phantom was shown at Meadow Brook, which was the mansion that John Dodge built for his wife Matilda, after the success of the Dodge Brothers car company. That’s because there’s a bit of a family connection.

Remember all of those references to “Mrs. Hugh Dillman of Detroit”? When I first saw the name in connection to the Rolls-Royce, it sounded familiar to me. After all, anyone in Detroit who ordered a custom Rolls-Royce in 1925 was likely some kind of automotive royalty. However, searching on the internet just got me pages of redundant results, almost all of them repeating the same phrase verbatim: “A Mrs. Hugh Dillman of Detroit.” Finally, thumbing through Charles Hyde’s “The Dodge Brothers: The Men, the Motor Cars and the Legacy,” I was reminded who Mrs. Hugh Dillman was. Better known as the former Anna Thompson Dodge, Mrs. Dillman was the widow of Horace E. Dodge, who started the Dodge Brothers car company with his sibling John in 1914, after more than a decade of being Ford Motor Company’s primary supplier. Besides being Henry Ford’s supplier, they also held an equity stake in his company. Early on, Henry gave the Dodges a 10-percent interest in Ford Motor Company in lieu of payment for the “machines” they built for him.

Both John and Horace Dodge died young, within months of each other in 1920, making their widows two of the wealthiest women in the world. Anna and Matilda, John’s widow, were left four fortunes. The Dodge brothers made $1.7 million in profits from supplying Ford. They earned another $5.4 million in dividends on their Ford stock.

In 1916, Henry Ford was hoarding cash to build the Rouge complex and also to deprive the Dodges, by then his competitors, of capital. The Dodges sued, forcing a multi-million dollar dividend payout. When Henry finally bought out his stockholders in 1919, the Dodges got $25 million for their 10-percent share of FoMoCo. Put those numbers in an inflation calculator and they get pretty big, but those fortunes paled in comparison to the $146 million Anna and Matilda were paid for their stock in Dodge Brothers by the Dillon, Reed & Co. banking firm in 1925, the year Anna ordered her Rolls-Royce. That’s the equivalent of almost $2 billion in 2016 dollars. Since there were far fewer people with that level of wealth, those hypothetical billions actually underestimate just how wealthy the Dodge widows were.

Even before she sold her interest in Dodge Brothers, Anna Dodge could easily afford a Rolls-Royce. She spent her summers at Rose Terrace in Grosse Pointe, the large mansion Horace had built for her on Lake St. Clair. Her winters were spent in Palm Beach, Florida. That’s where she met Hugh Dillman, the former actor (and likely gigolo) Anna married in 1926. Dillman worked as a realtor and director of the Palm Beach Society of Arts. Anna was 49 years old and Dillman was 43 when they married. They divorced in 1947.

One thing perplexes me about the story. The car is a 1925 model, yet Anna didn’t become Mrs. Hugh Dillman of Detroit (and Palm Beach) until the following year. If she ordered the car when it was new, she wouldn’t have been known then as Mrs. Dillman. Either she ordered the car some time after the chassis was built or over time the Dodge part of the story has become obscured.

The 1925 Phantom with the odd body is notable, but it’s really just a footnote in automotive history. Mrs. Dillman’s connection to Dodge Brothers, on the other hand, is undoubtedly the most significant thing about her.

Thousands of people have visited the Petersen museum every year and it’s been even more popular since it reopened after its recent redesign and renovation. Since it’s in the museum’s foyer, just about everyone who visits the facility will see the round door Rolls-Royce. If they decide to research the car, more than a few will read about Mrs. Hugh Dillman. However, they won’t know that the most interesting thing about her, at least from an automotive standpoint, isn’t the fact that she didn’t take delivery of the round-door Rolls.

.gif)

Great article, fascinating history and a stunning car. As other commentators have noted it was probably a nightmare to drive unless in a straight line – thankfully traffic was a bit lighter then!